Although we live in the present, as consumers, most of our spending and saving choices have time-related (‘temporal’) components to them. Because the present is immediate and the future is distant, we often discount the enjoyment that our future selves will experience, choosing to accelerate rewards to the present and delay costs to the future.

When choosing to splurge on a new pair of shoes today, not saving that money for tomorrow might seem like a small price to pay. But as tomorrows morphs into todays, consumers repeatedly eschew opportunities to save for the future. Procrastination comes all-too-easily and resisting spending inducements is difficult, which is the main reason why most consumers don’t have sufficient savings to survive even small-scale disruptions.

In 2023, the Federal Reserve found that 37 per cent of U.S. consumers would not be able to pay for an unexpected $400 expense with their savings. And in a PwC Employee Financial Wellness Survey, employees ranked ‘financial stress’ as a bigger stressor than all other life stressors combined.

To address these tendencies, we asked a novel question: Could mentally starting in the future and traveling back to the present in one’s mind alter how people think about themselves over time, thereby changing their financial decisions?

The existing research in this domain shows that decision makers mentally ‘travel through time’ in a linear fashion when making such choices, starting in the present and moving toward the future. But in a recent paper with my colleagues Katherine Christensen (University of Indiana) and Hal Hershfield (UCLA), we challenged this notion. We felt that changing the direction of mental time travel might affect the relationships of present and future selves across time—and thereby impact consumer behaviour. In this article I will summarize our findings.

Mental Time Travel

In everyday life, we make numerous decisions that involve selecting between outcomes that will be available at different points in the future. Such ‘intertemporal choices’ are inevitable, yet consumers often struggle to identify with different versions of their selves across time. For example, they often exaggerate the value of immediate rewards by overeating or overspending today, while planning to do better tomorrow.

When we think ahead to weekday evening dinners or next-day work meetings or look back on childhood memories, we are engaging in ‘mental time travel.’ Mental time travel allows people to travel across personal time, remembering the past and simulating the future.

In mental time travel, trips between the present and the future reveal different versions of a consumer’s self: the current self of today and the future self of tomorrow. Research shows that relationships between such selves can affect savings decisions. If consumers see their future selves as fundamentally similar and connected to their present selves, they are more likely to turn down smaller, earlier rewards and wait for larger, later rewards.

Also read: Revenge savings: New trend among Chinese youth

Even if people struggle to identify with the people they will become tomorrow or 10 years from now, these struggles can be overcome. Specifically, increasing the perceived similarity between present and future selves has been shown to reduce the intertemporal ‘discount rate’ and increase consumer saving.

As indicated, research has focused on only one mental pathway between these selves: from the present to the future. But just as people can start in the present and move forward in their minds, they can also start in the future and go back. In a pilot study, we asked Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) participants how they naturally travel through time, with the following prompt:

There are two ways to think about time when we think about what sort of things are going to happen in the future. One way is to start right now in the present and mentally travel ahead to the future. Another way is to start in the future and mentally travel backward to the present.

In line with the standard conception of time, participants were heavily skewed toward forward time travel: 83 per cent chose it as their primary mode of mental travel through time. But interestingly, just 27 per cent indicated that they only travel from the present to the future and never travel from the future to the present. This pilot study suggested that although beginning in the present is usually the default, it is not the only way to travel through time.

Research in spatial travel suggests that features of a journey affect how long the journey seems to take. Trips to a known destination (e.g. home) seem faster than trips to an unknown destination, even if both legs involve the same objective distance. Although this ‘going-home effect’ relates to trips through physical space, mental travel through time shares many of the same characteristics.

By integrating findings from mental time-travel research with the going-home effect, we reasoned that because people live in the present, the present self represents a temporal version of ‘home.’ By contrast, the future is a less certain destination because the future self exists away from the ‘home’ of the present self. If this theorizing holds, starting in the future and going home (to the present) might make the two points feel closer, which could induce a sense that the present and future selves are similar—that is, a temporal going-home effect.

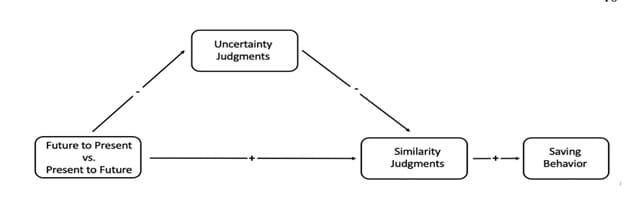

In sum, we felt that if traveling home in time, toward a certain, present self might make the future self seem more similar to the present self; this increased similarity between present and future selves may cause consumers to save more for the future.

With spatial travel, the going-home effect results in part from uncertainty about the away location relative to the home location. As previous research has shown, when participants don’t know what they will be doing later in a different room, they report stronger experiences of the going-home effect after they return to the initial room. The uncertainty of what would happen made the trip to reach it feel relatively longer.

Extrapolating to temporal travel, we posited that a temporal going-home effect could result from a similar sense of uncertainty about the future self, relative to the present self. Traveling back to a more certain destination (the present) might make someone feel closer and more connected to their selves across time, such that they appear more similar.

Our Research

We investigated the potential consequences for savings behaviour linked to forward and reverse mental time travel. Across 20 studies, we manipulated the way consumers travel mentally through time, in an attempt to increase both feelings of similarity with their future selves and saving intentions and behaviour.

We first examined whether changing the direction people travel mentally through time affects the similarity they perceive between their current and future self. In Study 1, we established that, in comparison to mentally traveling from the present to the future, traveling from the future to the present can affect similarity judgments across a six-year time horizon. Moreover, the effect of traveling from the future to the present affected judgments of similarity relative to a control condition. In three additional studies we replicated this effect across one, five and 10-year time frames.

Also read: Life hacks you need to know to save money while studying abroad

Next, we sought to identify the underlying mechanism for this. Study 2 showed that uncertainty linked to the ‘destination self’ accounts for the relationship between mental time-travel direction and similarity judgments. It also provided evidence that reducing the uncertainty of the destination self increases perceived similarity across a 10-year time horizon.

In Study 3, our primary aim was to examine whether mentally traveling from the future to the present could increase saving intentions. In this study, we found support for the effect of our invention on saving intentions. That is, participants who traveled from the future to the present reported a higher intention of saving when offered an introductory 5% savings rate, were more likely to invest windfall gains by buying a Treasury bill and were less likely to plan to spend all the money now.

The effect of mental time-travel direction on financial decision-making was not limited to 10-year savings goals. In Study 4, we examined whether starting in the future and mentally traveling back to the present affects consequential saving behaviour. Our aim was to pilot test the effect of mental time-travel direction in a consequential context. These findings provided preliminary evidence that traveling from the future to the present increases the likelihood that consumers will deposit real money in long-term savings products.

In partnership with a financial technology company focused on college savings, we further investigated the impact of mental time-travel direction on savings behaviour. As predicted, relative to participants in the present-to-future condition, participants in the future-to-present condition were more likely to complete the onboarding user flow and receive $10 investments in their college savings account.

Across mental time travel directions, participants traveling to a certain destination indicated higher similarity between their selves than participants traveling to an uncertain destination. A small effect of direction implied that participants in the future-to-present condition sensed greater similarity on average than participants in the present-to-future conditions.

We also found an interaction between time travel direction and uncertainty, such that the effect of traveling to a certain (vs. uncertain) destination self was higher in the future-to-present condition. Overall, we found further support for uncertainty as a driver of the relationship between time travel direction and similarity judgments.

Key Takeaways

Because consumers frequently fail to save for the future at the rates they say they desire, we investigated a novel intervention to help close this gap: altering conventional mental time-travel directions, by traveling back to the present from the future.

Across 20 experiments we demonstrated that mental time-travel direction affects how similarly consumers perceive their current and future selves and, in turn, the actions they take on behalf of those future selves.

Also read: It is time to recognise the value of unpaid care work in economic growth

Relative to mentally traveling from the present forward to the future, traveling from the future back to the present increased consumers’ perceived similarity between selves across time. Moreover, we found that uncertainty is a primary mechanism that underpins this effect. Ultimately, we established that backward mental time travel increases saving—albeit with small effects—in both hypothetical lab studies and incentivized field contexts.

Our findings contribute to several streams of research. First, work on future self-continuity implies that when consumers feel psychologically similar to their future selves, they discount the future less. Although present and future selves are, by definition, separate, theorizing in this arena documents how and why people might regard them as more connected.

We also contribute to the marketing literature on the going-home effect, which to date has been restricted to the spatial domain (i.e. felt distance between one place and another varies as a function of direction of travel.) Whereas trips through physical space often are measured in time (‘How long does it take to get there?’), trips through time often are measured in psychological closeness (‘How similar do you feel right now to yourself in ten years?’).

Also read: 4 food items you can freeze to save money

We examined how traveling back to the present (i.e. the temporal home) affects closeness across time and found that, like travel through space, travel through time seems closer, and the two selves feel more similar, when traveling ‘home’ (to the present) than when traveling ‘away’ (to the future). This effect is driven by the certainty of the destination self.

Uncertainty is fundamental not only to how consumers traverse time and space but also to how they make comparisons across different entities. Accordingly, we also advance the literature on ‘similarity judgments.’ Similarity judgments often compare better-known concepts (prototypes) with lesser-known concepts (variants).

Research on feature matching also indicates a similarity–judgment asymmetry as a function of comparison directions. For example, a friend is likely to be judged as more similar to oneself than the self is to a friend. This asymmetry arises because when people start with more uncertain, lesser-known concepts and compare them with more well-known concepts, they know fewer features, load fewer features, and then identify a higher percentage of loaded features that match.

To our knowledge, our research is the first to test this similarity asymmetry across time, in which one component of the comparison—the future self—does not yet exist. Even though the future self exists only once the present self ceases to exist, we found this similarity asymmetry still persists. By reversing the standard comparison—that is, by starting with the future self and comparing it with the present self—interventions can increase perceived similarity between selves across time.

Finally, our research contributes to the literature on ‘backward planning,’ which indicates that working backward from a goal to the present can lead to more realistic estimations of task completion time. When planners start in the future (with their goals) and move back to the present, they arrive at longer time estimates for project completion than when they start in the present and move forward in time. Thus, compared with forward planners, backward planners are more likely to realize they need more time to achieve their goals and make the changes they want.

Prior backward-planning research has investigated tasks that already are planned or in process; in contrast, we featured backward travel as a more general phenomenon, suggesting that traveling backward can create value even for consumers who do not already have savings plans.

Compared with forward travelers, travelers who mentally go back to the present judge their future selves as more similar to their current selves, seemingly because traveling back to this known destination self leads to a sense that the future and present selves are not very different. Furthermore, when consumers’ future selves feel psychologically closer to their current selves, they are more likely to commit to saving and making investments to help their future selves.

Managerial Implications

Our research has implications for companies, governments and individual decision-makers seeking to reduce savings shortfalls. Our field studies indicate the potential of mental time-travel directions to drive behavioural changes—in this case, among millennial investors in Sweden and investors in a college savings plan in the United States. Similar interventions might assist other institutions that seek to enhance future-oriented investments. For example, early claims of U.S. Social Security benefits can reduce retirees’ benefits by as much as 30 per cent over their lifespans.

The time at which this intervention takes place may be critical, and future research could examine both timing and age effects. For example, in a retirement context, an intervention six months before beginning retirement may be too late to shift judgments, while 30 years before retirement may be too soon.

Our findings also might apply to consumer and student loan debt. Temporal discounting not only affects the rates at which people save but also how much they choose to borrow and repay; research suggests students do not aim high enough and as a result may not borrow enough or invest enough in their education. A simple mental time-travel manipulation—before asking students how much they want to borrow—might change loan amounts.

In closing

Although human minds may tend to start in the present before moving to the future, they appear capable of more elaborate maneuvers. We offer reverse mental time travel as a promising intervention that alters how consumers relate to and make decisions for their present self and the self they will one day become.

My co-authors and I believe that traveling back to the present might also exert similar effects in non-financial domains that benefit from greater perceived ‘future similarity’—including healthy eating, education, healthcare and exercise.

Sam Maglio is a Professor of Marketing and Psychology at the University of Toronto Scarborough, with a cross-appointment to the Rotman School of Management. His co-authored paper, “Back to the Present: How Direction of Mental Time Travel Affects Similarity and Saving,” was recently published in the Journal of Consumer Research. The complete paper is available online.

[This article has been reprinted, with permission, from Rotman Management, the magazine of the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management]