Ramiz Khan, 48, lies in a Jammu hospital, his body torn by shrapnel from a blast that claimed the lives of his 12-year-old twins, leaving him to mourn their loss through a haze of painkillers. The explosion, which was part of the retaliatory strike by Pakistan following India’s Operation Sindoor, struck their home in Poonch, a rugged district nestled in the Pir Panjal hills and perilously close to the Line of Control (LoC), on May 7, weeks after the twins’ birthday. Ten days later, when Khan regained consciousness, his wife, Ursha Khan, broke down at his bedside. “Our world has ended,” she told him. The couple had relocated from their village in Mandi tehsil’s Kulani to Poonch district headquarters four months ago, seeking a better future for their children.

Their tragedy lays bare a grim question: Why are civilians so vulnerable at the LoC, and what will it take to protect them from the next inevitable flare-up?

The Union Ministry of Home Affairs had directed States to conduct a nationwide civil defence drill on May 7. But the operation was covertly launched on the night of May 6-7. As a result, families like the Khans were left uninformed and vulnerable in districts bordering the LoC—Rajouri, Poonch, Baramulla, Kupwara, and Bandipora. According to Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Omar Abdullah, Poonch bore the brunt of the violence, accounting for 20 of the 27 fatalities reported from the Union Territory. Over 70 others were injured, and thousands of homes, vehicles, and properties suffered damage in cross-border shelling and firing.

During the military standoff, as in times past, the thunder of war drums echoed triumphantly from distant television studios. In contrast, the anguish of LoC dwellers rose like faint wisps of smoke—barely perceptible and quickly dispersed by the heedless winds of a national spectacle.

‘A new normal’

On May 11, a press note issued by the Union Ministry of Defence hailed the operation: “It is a proof that whenever India acts against terrorism, even the land across the border is not safe for terrorists and their masters.” Another statement issued on May 14 lauded “The Rise of Aatmanirbhar Innovation in National Security”. Underscoring the role of the Integrated Counter UAS (Unmanned Aerial Systems) Grid and Air Defence systems in neutralising drones and missiles, it praised India’s defence indigenisation, highlighting how indigenous technology—from air defence to drones and net-centric warfare—proved crucial. The blend of private innovation, public execution, and military vision had strengthened India’s defence and established it as a 21st-century hi-tech military power, it added.

Also Read | The LoC is calm again, but Kashmiris still live under the shadow of war

Yet, for all the celebration of technological prowess and tactical success, the state failed to protect the lives of civilians in areas along the LoC. The residential areas along the 201-kilometre stretch of the International Border (IB) —from the Jammu-Sialkot sector at the Punjab-Jammu junction to Akhnoor—and particularly the nearly 734 kilometres of the LoC remain as unsafe as ever.

Surinder Mohan, who teaches at the Department of Strategic and Regional Studies, University of Jammu, and is author of Complex Rivalry: The Dynamics of India-Pakistan Conflict (University of Michigan Press, 2022), said: “Pakistan may seek to normalise such firing to internationalise the Kashmir issue. Civilians in areas along the LoC are at a greater risk now. Historically, from 1990 to 2016, Pakistan has deliberately targeted civilian zones to cause casualties and damage to properties. With a power asymmetry against India, Pakistan could exploit the terrain advantage along the LoC to destabilise the region and pressure India into resuming dialogue on Kashmir.”

Security analysts and local residents believe that Operation Sindoor signals a strategic shift—“a new normal”—where military actions may occur without warning, intensifying unpredictability of life along the western border. The cross-border firing in the wake of ceasefire violations was once largely confined to the LoC and the Jammu sector—referred to as the “International Border” by India and “Working Boundary” by Pakistan. Traditionally, the conflict in these areas involved “small arms and artillery fire, which, while disruptive, primarily impacted local border populations only”, said Pravin Sawhney, defence analyst and editor of Force magazine. He added that the “recent conflict has normalised the use of drones, rockets, and missiles—significantly extending the range and impact of hostilities”.

Defence Minister Rajnath Singh, while addressing Indian Army soldiers at Badami Bagh Cantonment, Srinagar, on May 15, said: “The Prime Minister has redefined India’s policy against terrorism, and any attack on Indian soil will be considered an act of war.” But experts point out that the lack of clear thresholds makes this stance ambiguous, allowing discretionary military responses without defined criteria and thus raising concerns over transparency and proportionality.

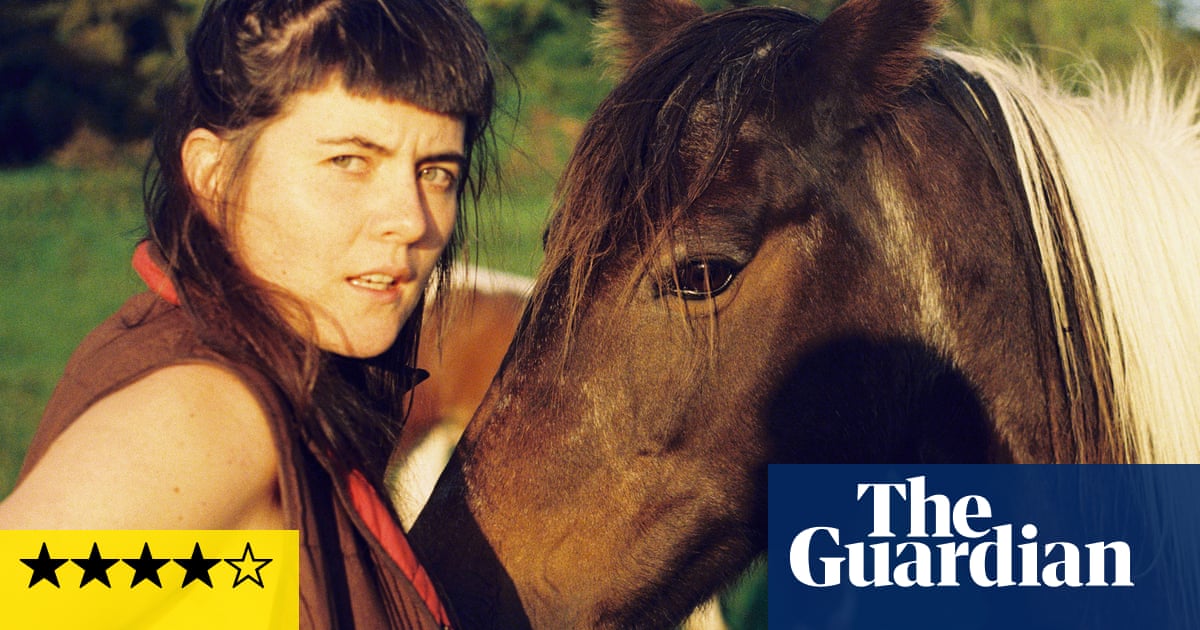

The twins Zian Khan and Urwa Fatima, who died on May 7, 2025, weeks after their 12th birthday, during Pakistani artillery shelling in Poonch district, in a photograph saved in the mobile phone of a relative.

| Photo Credit:

PUNIT PARANJPE/AFP

Pakistan has suspended the Simla Agreement (1972) in response to India suspending the Indus Waters Treaty (1960). Sawhney warned that without a formal ceasefire, any renewed hostilities could escalate rapidly, potentially involving long-range missiles and deeper territorial incursions. “While both nations have had missile capabilities since the 1980s, Operation Sindoor marks their first significant operational use. Strategic lessons will be drawn, but the situation is extremely dangerous,” he said. “The border populations, especially in Jammu and Kashmir, will suffer most. India and Pakistan now stand on the edge of war, with a lowered threshold for conflict and heightened threat levels.”

Unlike other border States such as Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Punjab—which have remained largely peaceful—the border areas of Jammu and Kashmir experienced only a brief period of relative calm in recent years. An agreement between the Directors General of Military Operations (DGMOs) of India and Pakistan to strictly observe all existing agreements and ceasefire protocols along the LoC and other sectors, which became effective from the midnight of February 24/25, 2021, brought relative peace to the region. Prior to this agreement, ceasefire violations had peaked on two notable occasions. The first was after the 2016 Uri attack, when Indian Army Special Forces conducted a surgical strike across the LoC, targeting terrorist launch pads. The second followed the 2019 Pulwama attack, when the Indian Air Force carried out an air strike on a Jaish-e-Mohammed camp in Balakot, Pakistan.

Caught in the crosshairs

Defence expert Major General Yash Mor (retd), who has served in the region, told Frontline: “Evacuating entire villages along the LoC in anticipation of hostilities isn’t practical. The only real deterrent is a strong, decisive military response that forces the adversary to rethink targeting civilians. Operation Sindoor marks a paradigm shift in our counterterrorism doctrine. We must carry forward this assertiveness unapologetically.”

Emphasising the need to upgrade public services and healthcare in border areas, Maj. Gen. Mor said, “It is critical for national security and community resilience. A robust, transparent system for swift financial compensation is essential to address economic losses from shelling. Crops, homes, and livestock are often lost, pushing already vulnerable families deeper into hardship. India has the resources to ensure such compensation is prompt, transparent, and adequate—we are not a poor country. Most importantly, a dedicated administrative framework is needed to coordinate security, development, and welfare initiatives, overcoming bureaucratic inertia, corruption, and political neglect in border regions.”

In a press statement, Shazad Ahmed Malik, chairman of the Jammu and Kashmir Border Area Development Conference (JKBADC), alleged misappropriation of Central funds meant for the welfare of border residents. The Central government had allocated hundreds of crores over the past decade for constructing underground bunkers in border areas, he said, adding: “A significant portion of these funds was siphoned off by corrupt officials in collusion with certain local politicians, leaving vulnerable communities exposed and unprotected.” Calling for accountability and transparency, he said the government should send independent experts to assess the situation on-site and identify suitable locations for new bunkers.

Chief Minister Omar Abdullah has announced an ex-gratia payment of Rs.10 lakh for each of the affected families. He promised that compensation for damaged properties, including houses, shops, and religious sites like madrasas, temples, and gurdwaras, would be provided on the basis of damage assessments that are expected to be completed soon.

The demand for relocation of border residents to safer locations has resurfaced. Congress leader and former Deputy Chief Minister Tara Chand has urged immediate relief for border village residents affected by intense cross-border shelling and drone activities. “We demand 10-marla [approximately 544 sq ft] plots and Rs.5 lakh for families living within Pakistan’s firing range to support their relocation to safer border areas,” he said. In the 2014 Lok Sabha election, the BJP had promised “5-marla plots” to border families in peace zones. Later, the ruling party backtracked on this promise, citing concerns raised by security forces.

Through the windshield of a bus damaged by cross-border shelling between India and Pakistan, in Poonch on May 9, 2025.

| Photo Credit:

REUTERS/ANI

On May 12, in a national address, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said India’s recent counter-terrorism operation sets a new standard, outlining three security doctrine pillars: decisive retaliation targeting terror hubs, zero tolerance for nuclear blackmail with precise strikes on safe havens, and no distinction between terrorists and their state sponsors. Modi announced that India had “temporarily paused” its retaliatory operations targeting militant and military sites in Pakistan. Stressing that terrorism is incompatible with dialogue, trade, or shared resources like water, Modi clarified that future talks with Pakistan would focus solely on countering terrorism and addressing Pakistan-Occupied Jammu and Kashmir (PoJK): “Terror and talks cannot go together… Terror and trade cannot go together…. Water and blood cannot flow together.”

Though residents who had fled to safer zones have started to return home after an intense and nerve-wracking week, a sense of unease lingers. They remain wary, fearing the borders could flare up again at any moment. Reacting to Modi’s speech, Yeshua Moser-Puangsuwan, an activist associated with the movement to promote humanitarian disarmament, told Frontline: “Given Modi’s latest statement it may not be over yet.”

Also Read | Ceasefire and Jammu’s smouldering anger

After the December 2001 attack on Parliament by Pakistan-based terrorists, India launched Operation Parakram, mobilising 8,00,000 troops along the western border. The operation, aimed at pressuring Pakistan to curb terrorism, led to heavy militarisation and landmine deployment, while residents stayed in migrant camps away from their homes. India’s border with Pakistan comprises three segments: the International Border (IB), spanning about 2,400 km from Gujarat to the Chenab river’s north bank in Akhnoor, Jammu; the LoC, covering 740 km from Akhnoor to Point NJ 9842 in Siachen; and the Actual Ground Position Line (AGPL), a 110-km stretch in Siachen marking troop deployments. In Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan calls the IB the “Working Boundary”, reflecting its stance that the Union Territory is a disputed territory.

The fence, technically called Anti-Infiltration Obstacle System (AIOS), installed after Operation Vijay (1999), commonly known as Kargil War, along the IB and the LoC, was constructed several kilometres behind the zero line. This was due to the 1949 Karachi Agreement, which prohibits new defence constructions within 500 yards of the LoC. As a result, thousands of hectares of farmland in Punjab and parts of Jammu and Kashmir now lie beyond the fence on the Pakistani side, while numerous residential villages along the LoC also find themselves cut off, stranded on the other side. The LoC residents in these areas, therefore, live under strict surveillance and exercise restricted movement owing to the extensive security apparatus. As part of ongoing work on border fortification, now a new Comprehensive Integrated Border Management System (CIBMS), also called smart fence, is being set up in some areas.

The decades of continuing militarisation have severely impacted local communities, leading to the loss of agricultural land and restricted access to natural resources. In 2018, the Kathua-based Border Welfare Committee petitioned the Jammu and Kashmir High Court, demanding that security forces either return unused agricultural land or provide appropriate financial compensation. However, farmers in many forward areas report receiving no relief, as the case remains pending. Residents along the LoC have similar complaints.

Lingering shadows

Despite the Army’s efforts to clear undetonated explosive weapons left from the recent flare-up, concerns persist about war remnants posing risks to unsuspecting civilians, especially children. In almost every LoC village, one comes across people who have fallen victim to abandoned unexploded ordnance and have lost their limbs and eyes. “Unexploded ordnance [UXO] remains a severe hazard near the LoC,” said Yeshua, who is also editor for the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, a project of Mines Action Canada. “Civilians returning to shelled areas face life-threatening risks from hidden explosives.” Emphasising UXO clearance and civilian risk education as urgent priorities, he added, “Without these, the human toll of this conflict will persist long after the shelling ends.”

He noted concerns that both sides may have used cluster munitions and pointed out that landmines planted along the LoC frequently injure soldiers, civilians, and livestock. Operation Parakram (2001–2002) had led to extensive mine-laying along India’s western border, posing long-term risks to civilians and soldier.

Also Read | Fragile peace, persistent tensions, and the limits of diplomacy

Water has emerged as a “strategic lever” in India-Pakistan relations. Mohan warned that this is potentially dangerous. “India’s potential weaponisation of water access could prompt Pakistan to retaliate through military or proxy means, escalating tensions,” he said. He pointed out that that the Indus Waters Treaty and Simla Agreement serve as critical “crisis buffers”. These agreements, while not perfect, help manage tensions. Undermining them risks removing vital safeguards against conflict, heightening regional instability.” Observing that “the absence of dialogue creates space for miscalculation, exactly what both sides must avoid”, Mohan said India should leverage its global partnerships to isolate Pakistan economically.

Operation Sindoor may provide short-term deterrence, but lasting peace in Jammu and Kashmir hinges on deeper ideological and geopolitical shifts in Pakistan. As long as Islamabad views Kashmir as the “unfinished agenda of Partition”, its use of terrorism as statecraft is unlikely to end, according to security analysts. Although tactics may evolve to avoid triggering large-scale responses, the underlying threat remains. Researchers at Delhi-based Institute for Conflict Management commend India’s counter-terrorism model, noting a significant decline in fatalities—from 4,011 in 2001 to just over 100 in 2024. Strategically, they argue, India has been gaining ground, though the goal of “zero-terrorism” remains unrealistic. According to them, stray attacks may persist, but the path forward lies in sustained internal vigilance and consistent external pressure on Pakistan.

Commenting on Operation Sindoor, Pravin Sawhney, who has co-authored “Operation Parakram: The War Unfinished” (Sage Publications, 2003) with Lt. Gen. V.K. Sood, stated: “We’ve achieved no significant military objectives. Instead, we’ve exposed the Indian Air Force’s limitations, much like during the 2019 Balakot strikes.” Following the Pahalgam terror attack, Prime Minister Modi visited poll-bound Bihar on April 24, shortly after returning from Saudi Arabia, to address a public rally. “While there may have been political benefits, with the Prime Minister quickly shifting from international diplomacy to domestic rallies—the military cost is significant,” Sawhney said. “The real concern is this: we are now living the war, not peacetime. In this dangerous new reality, we must be careful not to confuse political optics with strategic success.”