On May 10, India and Pakistan declared a ceasefire following four days of escalating military hostilities. This came in the aftermath of the April 22 terrorist attack in Pahalgam, in which 26 people were killed, and India’s reprisal military attacks inside Pakistan after that, called Operation Sindoor.

Srinath Raghavan. The military historian and author says that “deterrence by denial” in the form of hardening India’s counter-terrorism infrastructure and making moves to deny Pakistan the ability to weaponise the Kashmir problem was critical.

| Photo Credit:

R.V. Moorthy

Srinath Raghavan, a military historian and author of several books, notably War and Peace in Modern India, spoke to Frontline about how terrorism could not be solved through “deterrence by punishment” alone. He added that “deterrence by denial” was just as important in the form of hardening India’s counter-terrorism infrastructure and making moves to deny Pakistan the ability to weaponise the Kashmir problem. Edited excerpts:

Will the ceasefire hold?

Well, it looks like the ceasefire will hold because both India and Pakistan, at a political level, have said that their immediate objectives for this particular crisis have been achieved. So, there is definitely, at the political level, a desire not to see a resumption of hostilities at full scale. At the same time, we have been seeing reports about violations of the ceasefire by Pakistan—firing, drone activity, etc. Again, I’m in no position to verify how accurate these reports are.

But I will say this much. Looking at the ends of various conflicts that we have fought in the past, ceasefires always take a little bit of time to stabilise. People tend to be trigger-happy and tend to be a little jittery. There is always some very local jostling for advantage even as every conflict comes to an end. And this is practically true of all the wars and crises that we fought. Even in Kargil, for several days after the ceasefire was happening, there used to be sporadic movement, exchange of fire, constant conversations between the Directors General of Military Operations on either side that were required to make sure that it was stabilised. So, I wouldn’t overread what is happening now. It seems to me to be well within the pattern. And the most important thing is that, at the political level, it seems like we do have a ceasefire.

The signing of the ceasefire itself has led to a lot of anger in India, especially in the BJP’s core constituencies and even in some sections of the Indian strategic community including the Indian military, that we have in effect “snatched defeat from the jaws of victory”, as one commentator has put it. Did India have a choice of actually continuing the hostilities until a victory had been extracted from it?

Well, victory in any military context, whether it is a war or a crisis, is only to be measured based on the political objectives for which that particular conflict is being waged. If our political objective was a total defeat and destruction of Pakistan, then yes, perhaps we should have continued this conflict till that particular end was either attained or it became absolutely clear that it was unattainable in this case. However, it does seem—and I’m going by the official briefings which have been given by the military spokesperson—the Director General of Military Operations in his press conference the other day also explained [that] the Prime Minister has given a speech. None of it suggests that our objectives were that much more than instilling a degree of fear and caution in Pakistan, that support for acts of terrorism against India will go unpunished, that you cannot have impunity, and that we will impose costs on you in order to get you to desist from these kinds of activities. So that seems to have been a much more limited objective.

In fact, in today’s newspapers, I saw articles by former senior military officials, which I suppose reflects the thinking within the military, which is to say that our objective was not to even expect that Pakistan would entirely dismantle its terrorist infrastructure. We wanted to punish; we wanted to cause damage to terrorist infrastructure and send out a signal that in the future, this punishment will be forthcoming. And that is all towards the end of establishing deterrence or preventing the recurrence of such attacks, which I think is a much more limited, circumscribed objective than this idea that we have to once and for all solve the problem of our relations with Pakistan, whatever that might mean.

This is the third punitive strike against Pakistan in nine years. The first was in 2016, the surgical strike after the terrorist attack on the Uri brigade headquarters. The next one was in 2019 after the suicide bombing in Pulwama, which killed 40 CRPF [Central Reserve Police Force] personnel. And now this one after the terrorist attack at Baisaran Valley in Pahalgam. So, every attack has been about deterrence, about punishing Pakistan, about getting it to cease and desist from enabling terrorists or even using them directly as proxies in India. So, what do you think Operation Sindoor really achieved?

Well, there are two questions here. The first question is whether military strikes of the kind that we’ve carried out since 2016 are, by themselves, going to solve the problem of terrorism for us. And for a variety of reasons, I believe that is not the case. This can be one part of a larger package of responses that we have, but it is unlikely that it can solve.… I’d say upfront: unless and until we harden our counterterrorism infrastructure within Jammu and Kashmir itself, commensurate to the new kind of situation that exists there, we are likely to see that some of these sporadic attacks will continue because it is relatively easier and low cost for terrorist organisations and their sponsors to carry out these kinds of attacks.

As far as Operation Sindoor [is concerned], I think we have demonstrated that India has both the capacity to attack Pakistan and impose costs, and that we have the will to do so. So the capability has been demonstrated for carrying out standoff strikes against a range of targets, not just terrorist infrastructure but also headquarters of organisations that were supporting terror, wider military installations across the Punjab and other parts of Pakistan. So I think both geographically and in terms of weapon systems we’ve deployed—and I’m here just going by reports of what we see—weapon systems like BrahMos, which apparently struck their target, particularly the Nur Khan Air Force Base in Pakistan, which suggests that some of the technologies that we have developed with the Russians jointly, which is indigenous, a cruise missile system, has shown its capability in a conflict situation. So there have been a series of such things that we have achieved.

Now the question is whether we expect that these attacks will, in a sense, restore deterrence. But that puts too much of a burden on just these kinds of actions. Deterrence always operates at least two different levels. There is what we call deterrence by punishment. So you punish someone for an act, thereby sending a message that, please do not do this in the future, otherwise you will get the same retaliation. A lot of domestic crime is about deterrence by punishment, because that’s what the laws are there for, that’s what the police are there to implement the laws.

But there is also another form of deterrence that we call deterrence by denial, which is to say that you harden your defensive capabilities to the point where it becomes much more difficult for the other side even to carry out attacks. And that is at least as important as deterrence by punishment. To give you the analogy, if you want to protect your house from being burgled, you won’t just depend on the laws of the land to deter potential burglars. You also want to put up fences, you want to put up electrification, you may want to have security guards. So, deterrence for denial is at least in fact much more important when it comes to things like terrorism. Precisely because terrorism is a very low-cost activity for the other side to carry out, and there are a number of groups, a lot of floating capability to carry out these kinds of things. So if you are really serious about deterring terrorism, we need a combination of denial and punishment. Because of the background of the present crisis, we are very much focused purely on the punitive aspects of what our response should be. I think the denial-based aspects need at least as much consideration.

Also Read | In dealing with Pakistan, India has to choose from a menu of bad options: T.C.A. Raghavan

Over the last few days, one phrase that has been used a lot is that Operation Sindoor has established a new normal. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has also used this phrase in his address to the nation. The other is that India will treat every future attack as an act of war. If the signal here is that India will not hesitate to carry out punitive attacks, has India sufficiently demonstrated conventional capacity to do this without crossing and without the danger that this can cross the nuclear threshold?

Let’s take it one by one, right? The first question is, what does it mean to say that we can treat every future terrorist attack as an act of war? And again, I think the Prime Minister is basically trying to establish what you would think of as a red line to say that if any activity which sort of transgresses that line, then it will invite retaliation of a very significant kind. And I don’t think we need to literally sort of read it to say that India is going to go all out in war. You are saying that it will invite military retaliation.

The second thing is about saying it’s a new normal. And again, I’ve seen that phrase being used in official language but also in some of the sort of commentary that we have seen from people who are kind of closer to the system. Again, I do wonder what it means to say that we are capable of continuous strikes on Pakistan. Because the way I understand these situations is that from a crisis to a crisis, if you really want to make sure that you are sending a strong message, the message has to get stronger. Otherwise, there is nothing much to be done. If we had done a response similar to what we did in Balakot in 2019, which was a single standalone strike, then perhaps the message would not have been as strong. But this time we have struck a variety of targets.

Geographically, we have used different kinds of weapon systems and we have not even hesitated from striking areas, terrorist areas which are close to population centres, all the while allowing that our intent is not escalatory, etc. But again, there has been both a geographic and weapon systems-based escalation of our capabilities. So if I may use a mechanical metaphor, with every turn the screw will get tighter. With every crisis, the threshold of using force will have to increase. That is in the logic of things.

Pakistan has its own capabilities. This time around also, it has demonstrated that it can impose costs on us even as we try to punish it. And you can be pretty sure that the Pakistanis will prepare for similar contingencies and even better, even higher sorts of levels of use of force for the next crisis as and when it comes around. So, I do not believe that the threshold is going to be the same: it will increase, and that is the problem. If we are going to say that this is a new normal, please remember that the new normal will get old very soon. And then there has to be a newer normal. And that newer normal takes you further up the chain of escalation. And then all other kinds of possibilities of where these conflicts could end up will come into play much more quickly than they did this time.

During this particular conflict, did you personally think that it was going to end in a nuclear conflagration?

No, I don’t think so. Because the nuclear threshold, as stated by Pakistan, is a significantly higher one. If we go by what the Pakistanis have said in the past, and which stands to reason even without having their assurances, is that nuclear weapons will be something that they will use if they feel that the very political existence of Pakistan is at stake, etc. That is a very different level at which we are talking about it. But the general concern—and it was not necessarily a concern that I had during this particular crisis— when it comes to crises involving nuclear powers is not so much about whether there is clear intent to use nuclear weapons, whether there is a rational calculation at play saying, “Oh, if we hit India, then India can destroy us, so should we not be using them at all?”

Rather, crises—and here I’m talking as a historian who has studied many of these things, not just in the India-Pakistan context but in many other contexts—tend to be very confusing situations. There is an absolute lack of clarity about the capabilities and the intentions of the other side. There is something called the fog of war, which obscures real-time understanding of what people are doing. So, if you get to certain kinds of weapon systems and certain thresholds of using force, the line between what is conventional and what is potentially nuclear can get blurred. And that is when action-reaction chains can set in, and things can get pretty sort of uncertain very quickly. So, we should not, therefore, overestimate our ability to stay in control of every situation or hope that the Pakistanis will be absolutely rational and in control as well.

Did you think that India had enough control over the escalation ladder in this particular conflict?

On this occasion, I would say that yes, the Indians did manage to make sure that the escalatory dynamic did not get out of control as far as they were concerned. Whether they had escalation dominance or not is the second order question. We’ll come to that in just a minute. But I think the Indian response at every time was calibrated. We kept saying that we are only responding to what Pakistan is doing at the same level, by which we mean what’s the kind of weapon systems, what kinds of targets, etc. And we kept saying that we do not want further escalation, which was a good thing.

But escalation is not a one-sided activity. It also depends on the other side. Escalation typically is an outcome of the interactive moves made by each side. When one side uses some force, the other one has to do more than the other one. The first party has to do more again. So, there is a sort of upward spiral, which is the way that we should understand this.

And the metaphor of the escalator itself is an interesting one. Imagine that you stand on an escalator, you can only get out at the top. There is a certain inexorable momentum to it. In our strategic discussions, we tend to sort of use the oxymoron of an escalatory ladder. Escalations and ladders are very different things. And we should never be so confident that this is like climbing up a ladder, an escalator.

You come down a ladder, but you can’t come down an escalator.

Or at least you can only go up to a certain point and then take the escalator back down. Right?

So that’s what you’re talking about: escalation dominance. Some international media reports also suggested that a turning point to the conflict came when the Pakistani leadership was reported to have summoned its National Command Authority after India hit the airbases inside Pakistan, notably Chaklala airbase, which is in Rawalpindi. And Pakistan denied thereafter that such a meeting had been summoned or that it took place. But if such a meeting was indeed summoned, what was Pakistan’s intention? Was it just signalling or did it actually intend to use nuclear weapons?

The Pakistani threshold, both in terms of what they have stated in the past but also what stands to normal kind of strategic political reason, is much higher. It will be a weapon of more or less the last resort, as it were, for Pakistan to secure itself. It is not something that they will contemplate using very easily. And again, if you notice the Pakistani press conference, the DG ISPR [Director General Inter-Services Public Relations] repeatedly kept saying that there should be no war between nuclear-armed neighbours, etc.

From the Pakistani perspective, however, I think it also stands to reason in a crisis like this to keep insisting that the nuclear threshold is not very far away. They have to kind of signal that in order to catalyse external intervention. Just as it stands to reason for India to say that we will not succumb to Pakistani nuclear blackmail— which is what the Prime Minister has also said—and this is again a posture that goes back a long time.

After the Kargil War, General V.P. Malik said in a seminar that the Kargil War has shown that there is space for limited conventional war against a nuclear backdrop. So we want to assert that there is a space. The Pakistanis want to deny that the space is as wide as we would want it to be, and they would want to catalyse external intervention. So the suggestion that the Nuclear Command Authority was meeting was intended to convey a message, particularly to the United States, which apparently till that point of time wasn’t taking the crisis quite as seriously as perhaps the Pakistanis would have liked, which I think is precisely what happened. So, the Pakistanis, we have to make a distinction between what they say with what they do.

Again, in a crisis, these things might be very difficult to disentangle. With all the benefit of hindsight, we can now look back and perhaps there is a lot more to be learned by us about how these things played out. But it does seem like once the Pakistanis had struck, or at least claimed to have struck, some Indian airbases, and following that, there was an Indian retaliation which struck their airbases. At that point, the Pakistanis felt that they had done enough to domestically be able to claim that they could call it quits. And the only way then to reach towards de-escalation quickly was to get external actors to get involved more seriously. And I think that the nuclear argument—that the Nuclear Command Authority is going to meet, etc.–they may well have perhaps intended initially to do it, but either way, the signalling utility of it was much stronger than the practical.

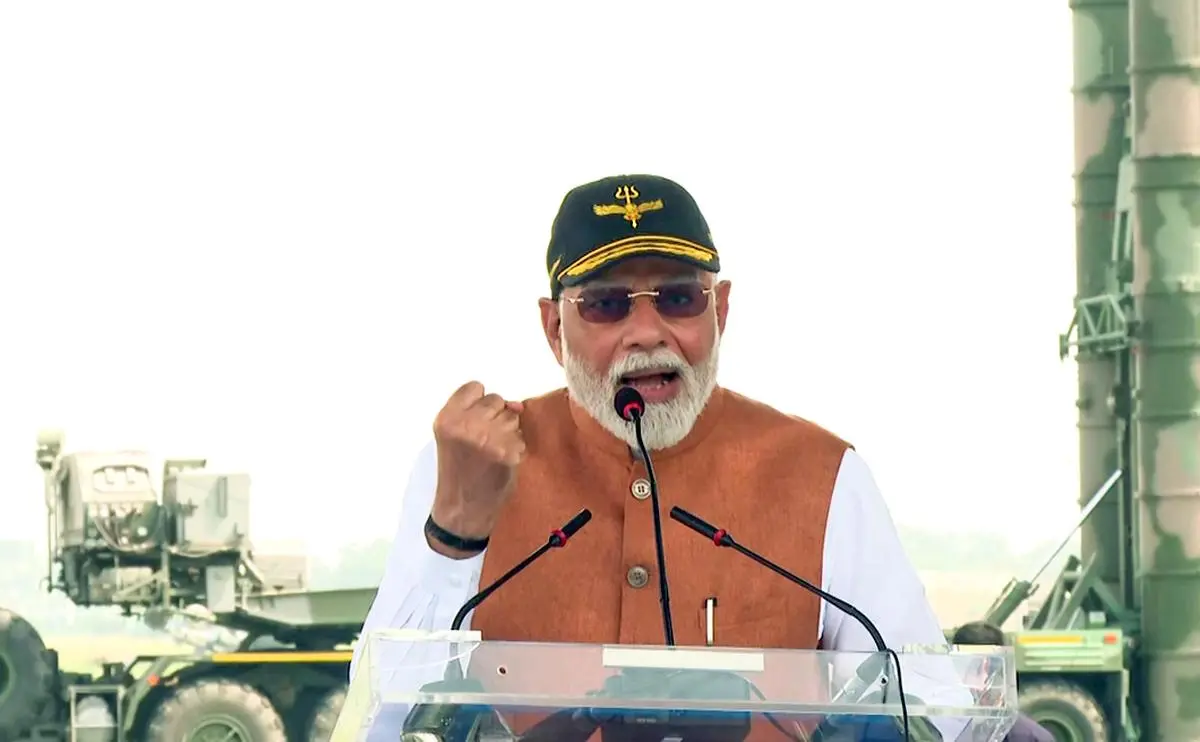

Prime Minister Narendra Modi addresses the soldiers during his visit to the Adampur Air Base, in Jalandhar on May 13, 2025. In a televised address to the nation a day before, Modi said that Operation Sindoor has established a new normal.

| Photo Credit:

ANI

One of the things that’s being said about India’s response after Pahalgam is that by announcing that India would punish the perpetrators that carried out the attack there, but leaving it there for two weeks, India lost the element of surprise that is usually crucial to any kinetic operations, thus handing Pakistan an advantage. Do you agree with this view?

At some level, I think even if the government—let’s assume hypothetically—had not said that they will do so, the general expectation was very much that there will be a kinetic response. And at least that was the expectation amongst a large number of people, whether we agree or disagree about the efficacy of those kinds of actions, simply because there has been a past pattern of that kind of use. We have signalled that kind of posture to Pakistan, but we have also signalled the same posture to our domestic audiences. So it stands to reason that some such action would have followed.

Again, getting the element of surprise in any of this is actually quite difficult because in 2019, we had never used an airstrike against a terrorist facility. Let’s remember that even that was not in PoK [Pakistan occupied Kashmir], that was in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Which is also Pakistani territory proper, not territory that we claim as part of India. But that was a one-off and the first time we did it.

This time around, the expectation should have been that the Pakistanis will be much better prepared. Therefore, you needed more time for preparation, more thinking through what we needed to do. But also this time, it took a little bit of time to make sure that we used capabilities which we could then demonstrate to the rest of the world quite clearly. That was again a bit of a question mark, which was constantly being raised because Pakistan denied that anything had been struck in 2019. So, this time around, we wanted to have a very clear thing, which was shown in the very first military briefing that we saw. But that element of surprise is difficult to achieve in these contexts, even if it is vital.

When he made his speech, Prime Minister Modi said that instead of supporting India’s strike against terrorism, Pakistan started attacking. India itself targeted our schools, colleges, gurdwaras, temples, civilians, and our military bases. The sentence is a little puzzling to me because it sounds as if India was expecting the Pakistani state, Pakistan, not to respond.

Actually, I would be very surprised if there was a baseline assumption that the Pakistanis would actually not respond at all. In fact, I’m pretty sure that the military plans would have been expecting a retaliation of some kind, you know, as a military, you have to prepare for the worst case scenario rather than hope for the best case scenario.

And see in Pakistan, there are multiple centres of decision-making and power. The civilian government is perhaps one of the weakest in the history of Pakistan and is already on the ropes as far as the economy and other things are concerned. The Pakistan Army itself has been under a lot of pressure from a variety of fronts. They’ve not managed to have reasonable relations with the Taliban. They’re having a serious problem on hand in Balochistan. The TTP [Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan] and other groups have kind of been nipping very hard on their heels. So, in this kind of situation, if the Pakistan Army were to show weakness or at least not attempt to sort of hit back and then claim a victory which was the normal course to expect, it would have been a very surprising thing actually.

So, the baseline expectation should have been that they will have as much compulsion. But I think what the Indians perhaps may have expected is that the Pakistanis will look for an easier off-ramp than perhaps war. What eventually ended up happening was that the conflict actually went on for perhaps longer than that. That was perhaps an expectation we could have had. But those are difficult things to predict upfront. We don’t know how a crisis plays out. We don’t know where the possible points to sort of actually escalate are. So it’s a little difficult to say what those expectations were, but certainly from the military point of view, they would have been prepared for a retaliation from Pakistan.

There have been several international media reports that have spoken about India losing anywhere between three to five aircraft. At one of the media briefings, when Director General of the Air Force Operations Air Marshal A.K. Bharti was asked about these reports, he said losses are normal in a combat scenario and that India had caused heavy damage to several Pakistani air bases. Does the damage we might have done to the Pakistani airfields compensate for the loss of the aircraft? It has not been officially accepted, but this seems to be an indirect acknowledgment that there were some losses.

At least there was not an outright denial, right? I don’t think the Indian government denied any of those reports. And those reports were kind of coming in pretty much from the time that the news of Operation Sindoor started flashing morning India time. The Air Marshal is right to say that in any conflict, you should expect losses and that there are things that we have done which also have to be taken into the balance sheet. But I hope and I’m reasonably confident that the Air Force will do its own kind of internal reviews on this situation because, at the end of the day, this was an operation that was planned and executed at a place and time of our choosing. As I said earlier, the element of surprise was always difficult to achieve. But if in the very first strike, the Pakistanis managed to impose costs of this nature on us… I’m not talking about the magnitude. I’m just saying that if they managed to sort of take down Indian aircraft and other things, then perhaps there is something for the Air Force to look carefully at and learn lessons from about how these operations were planned and executed.

There’s a famous saying by the Prussian General von Moltke, who said that no plan survives first contact with the enemy. That is absolutely true. The minute you are in war, all plans tend to. But that does not mean that you do not plan, nor does it mean that you do not learn the right lessons or the best lessons that you can once the dust of war is settled. And I really hope that the Air Force will, and I’m pretty sure they will do it. We’ve always done it in the past. There are always after-action reviews and other things that are carried out. The important thing is that the military learns the right kind of takeaways from this crisis because there will be crises to come in the future.

“If we are going to say that this is a new normal, please remember that the new normal will get old very soon. And then there has to be a newer normal. And that newer normal takes you further up the chain of escalation.”

So what are the lessons from this crisis?

At this point of time, it is very difficult to say because there is just so much that we do not know. And I’m here putting on my hat as a historian: even when you have so much material, your judgments tend to be quite tentative.

I meant military lessons.

The key military lessons to say are things which we should expect out of any such crisis or conflict, which is that Pakistan has again demonstrated a degree of ability to impose costs on us even as we exercise options to punish them. Not just technology, but their operational posture was such that they could do this. At the same time, we have managed to also sort of inflict costs on them and have used some new technologies which were perhaps deployed for the first time. And we should both learn that the threshold at which international intervention gets catalysed is still the fear of escalation to a nuclear conflict. And that should be very important because in the next crisis, the threshold of force will have to be higher. At that point of time, we are going to have an even smaller window because the crisis will start at a much higher level of escalation.

See, in 2019, you did one strike. This time around, you’ve done a bunch of strikes. Next time around, you have to do something more or something different, something qualitatively and quantitatively different. And that will mean that the Pakistani response will also be different because they would be expecting you. That is the way they will take away their learnings from this. So the next crisis will escalate rather more quickly. And therefore, we should be sort of prepared that we may not have even this much of a window to do what we want to do.

And by saying that this is a new normal and that every future terrorist attack will be an act of war, does this run the risk of handing over the levers of this conflict or of any conflict in the future to elements that want to start a war?

Well, certainly that is one potential implication. And again, you know, we have, in fact, made that possibility somewhat more difficult by saying that we will treat every act of terror as an ipso facto act which has been initiated as an act of war by the Pakistani state. So we have drawn a very tight link now between these, which also means that there is no onus on us to establish that these attacks actually have anything. So all of those expectations are thrown overboard. We will treat every act of terror as if it’s an act of war initiated by the Pakistani state, and that our reprisal is sure to come, and that this is the threshold from which things will begin. Then you are setting yourself up for crises which will escalate more quickly and more sharply, and perhaps will catalyse international intervention of other kinds as well.

I’m just speculating, but we need to put ourselves in the other side’s shoes from time to time when we think about military matters. Right? It’s not just about what we have done, but what they will do. If you are in the Pakistan military today, one of the strongest incentives you will have is to sort of acquire greater operational and strategic proximity to China. Because if it is the case that India is going to hit you automatically every time something happens and you have no desire to sort of wind down those assets, then you better prepare for other eventualities. And I think diplomatically the United States is the country to capitalise, but militarily, perhaps it will be China.

Again, I’m not saying that the Chinese will get involved in an India-Pakistan conflict simply at the behest of Pakistan, but as we have seen, the issue is not just this time around the use of Chinese technology, which has been reported, but the fact that Chinese operational concepts have been used by the Pakistan Air Force that could not have been done if there was not a degree of operational and military coordination between those two sides prior to this conflict. So, they have been sort of preparing and training to use these in certain ways.

The problem with a lot of analysis is that it tends to focus on technology. Technology is important, but the operational concept within which a technology is deployed in war is still more important. And the operational concepts which they have deployed seem to be those which are borrowed from the PLA [People’s Liberation Army] Air Force, which has created them for other kinds of contingencies like Taiwan. We need to be mindful of the fact that the Chinese [and] the Pakistanis will want to go further in this. So that has all kinds of implications for how our relationship with China plays out.

That said, the Chinese initially did condemn the attack, because they themselves have concerns about Islamist terrorist organisations in Pakistan, in China. And China doesn’t generally take this, but once it became clear that there was an Indian strike, etc, which was imminent, then we saw that the Chinese were willing to give more cover to Pakistan, particularly in the UN Security Council context. We did have a statement which was supportive of India and condemning the terror attack, but refused to sort of name the group which had claimed responsibility, etc. So, some degree of cover was given. And subsequently, when pointed questions were raised, the Chinese spokespersons have said that military action against India is unfortunate, etc. But frankly, given the nature of China-Pakistan relations, I would expect that they should do at least that much for an ally.

So my concern is that the way this crisis has played out and the expectations that it has set for more kind of sharper and perhaps shorter crises going forward, there may be now a greater degree of coordination between China and Pakistan about such contingencies in the future.

Indian Army soldiers walk along a road near Zojila mountain pass that connects Srinagar to the Union Territory of Ladakh, bordering China on February 28, 2021. Raghavan does not believe that the recent India-Pakistan crisis would set back India’s attempts at normalisation with China.

| Photo Credit:

TAUSEEF MUSTAFA/AFP/File Photo

So what does that actually do for the normalisation process that India started with China? What is going to be the fallout of that?

See, the normalisation process was driven by concern between India and China about their disputed territory and about China’s unwillingness to abide by understandings that had been reached in very clear, explicit terms. They overturned existing understandings, which led to greater deployment of forces on our side. Of course, they have also deployed. So, there is an interest now in slowly de-escalating and then finding a way back to other kinds of things. So that is a process that is halting, slow. It has taken a long time to even get this far. So, I do not believe that one way or the other, we should be too optimistic about where that particular process of de-escalation is going. It is going to take its time.

There are other kinds of challenges that we have in our relations with China, particularly on economic issues and so on. And in any case, at this point of time, the overall sort of Indo-Pacific situation has been kind of confused and scrambled by American policy that perhaps we are also just waiting and watching to see what is going to happen. So, I actually do not believe that this particular crisis is going to set back our attempts at normalisation with China. Those attempts were slow, halting, step by step, and that is the way they will proceed.

The other diplomatic fallout of this is that the President of the United States, Donald Trump, has claimed that he mediated the ceasefire, that he threatened to cut off trade with both India and Pakistan, and that he would also like to help India and Pakistan reach a solution on Kashmir. And India has denied these claims. India has always held that Kashmir is a bilateral dispute. And over the last few years, even this formulation has narrowed to the fact to the point that there is no scope for discussion on anything other than terrorists, terrorism emanating from Pakistan, and for the return of PoK. But is not the risk of internationalising the Kashmir issue inbuilt in any military action against Pakistan? Isn’t this something that we should have factored in as we went into this?

Again, I’m reasonably sure that we would have factored in some degree of internationalisation or gathering of international attention on this issue. But in the scheme of things, given the nature of the attack and what we wanted to accomplish, those were seen as more manageable problems. Perhaps at the diplomatic level, those could be happening.

Now, President Trump—his claims are, as with most things he says, you just have to wonder how much of it is fact and how much of it is hyperbole. But it seems clear that the Americans did make phone calls, get the two sides to talk to each other. The Indian account is that the Pakistanis were told by the Americans that they should take the first step to reach out. And again, whichever way you present it to domestic audiences, it doesn’t matter. The fact is that you have a ceasefire and that the American involvement, in a matter of several hours, actually has helped us to get to this point. And if President Trump wants to take credit for that, he’s entirely entitled to take that. Why not? At the end of the day, his administration has kind of put a blanket on this particular crisis. And again, I’m not so sure that it was that the Indians wanted a continuous escalation. So, from our perspective, it was useful to have an off-ramp at a point when we believed that we had made the point that we wanted to make by using military force in quite this way.

As far as the story of internationalisation, again it’s worth recalling that President Trump, I think in 2019, when the Indian government had more or less diluted and nullified Article 370, had even at that point of time said that he’d be more than happy to sort of sit with India and Pakistan, mediate a solution. And our response, which was given by the MEA [Ministry of External Affairs] spokesperson, was to say that this is a bilateral issue, that in the Simla Agreement, we had sort of agreed and so on.

As I see it, that remains our position. In fact, it is perhaps narrowed and hardened since. But there is one sticking point, or rather, there are two sticking points. One is that in this crisis, in response to our decision to hold the Indus Water Treaty on abeyance, the Pakistanis have said that they will also treat the Simla Agreement as in abeyance, right? Which means to say that they will not abide by the understandings of the Simla Agreement. The operative parts of that understanding in the current circumstance are the Line of Control, which is an agreed line between the two sides. It’s not an international border, but it is an agreed line. There is an agreement, the Suchetgarh Agreement of 1972, with maps signed, which we flashed on television when the Kargil War happened. And the Simla Agreement, one of the main intentions and outcomes of which was to bilateralise the problems and say that all measures should be taken to resolve bilaterally.

And we did that partly because, for several years before that, we were under a lot of continuous international pressure to say that we should speak to Pakistan. The Americans and the British put that pressure on us after the 1962 war when we turned to them for help against China. In 1965, the Soviet Union, after the mediation of the ceasefire in Tashkent, did convey to both sides that we need to sort of have a peaceful understanding, etc. So, one of our intentions of the Indira Gandhi government in 1972 was to make sure that we have an agreement from Pakistan that this will be discussed bilaterally. With Pakistan putting that in abeyance, it effectively means that there is no such mutually understood thing.

Now, that has two consequences. One, it means that Pakistan is at liberty to keep raising these at various international fora, drumming up support. My own expectation is that once the initial fever over this crisis subsides, it is unlikely that Pakistan will be able to gather that much support. But we should be mindful that in any future conflict or any crisis of this nature, this remains the international pressure point.

The second thing that we need to understand is that India is not in the same position that it was in 1962 or 1965 or any of those decades. Our relationship with the great powers has changed considerably. We matter a lot more to the United States, to Russia, and other countries for them to be able to pressure us to do anything that we do not want to do. Even though there has been no official refutation of the claims that India and Pakistan will meet at a third-party, neutral location. And when was the last time? Tashkent, 1965. I don’t think all of that is in the realm of possibility. I don’t think the government of India can be pressured to do any of that stuff.

But at the same time, India cannot unilaterally insist that this is a bilateral problem. That is also gone. So, there is always a window, not just for Pakistan to raise it, but for other countries to keep flagging it to say that India and Pakistan should talk. So this will be an irritant. It will be something that we will have to expend some degree of diplomatic energies in order to parry those kinds of claims. But that is the situation in which we find ourselves.

Just as we thought that we were over this problem, that after the abrogation of Article 370 we had actually successfully managed to convince the world that the Kashmir problem was essentially over and now it was India’s problem alone to sort out what remained internally in Kashmir and Pakistan had absolutely no say. So, it’s come back to a point where it’s sort of pre that act of abrogation. Do you see it as that?

I don’t actually, because I do not believe that the abrogation of [Article] 370 would have taken Kashmir away from the international spotlight to the extent that it existed. It was not the same as in previous preceding decades. That much I’ve said already.

Because see, 370 is effectively a move about the constitutional relationship between Jammu and Kashmir and the Union of India. That does not take away from the fact that India still claims that there is a part of Jammu and Kashmir which is under Pakistani occupation. We never said that by abrogating 370, we are writing off our claims to PoK. In fact, the problem cannot go away in an international sense till such time as either we agree that PoK is back with us or that we agree to sort of have a clearly defined international border. So 370, contrary to all the talk and commentary here in India, was never about removing Kashmir as a problem. It was about changing the nature of your relationship within the constitutional framework of India. And that gave you certain kinds of powers to deal with the internal security dimensions of it because, as a Union Territory, you also had more powers vested in the Union government for how you could deal with law and order, etc. But none of that would have been a solution to the Kashmir problem.

See, because there is a contradiction between saying that we want PoK back and that the Kashmir problem is solved. Both things cannot be said in the same breath. So, the international dimension of it will remain till such time India and Pakistan find a solution to the problem. In anticipation of a question. I may just say that I do not believe any such solution is possible in the near or even in the medium-term future. There are many problems in international politics that are not amenable to solutions. You can either manage them or you can endure them. That is the realm in which we are.

“The baseline assumption that Pakistan only matters to the world because of its strategic location has always been proven to be wrong, because Pakistan has reinvented itself from time to time in the sense of what makes it important.”

I wanted to ask you about the reaction of the world, not just the United States, but also of all its friends that India approached. And who counselled India and said that, well, you have to sit down and talk to Pakistan, and basically counsel both sides that they should show restraint and talk this out. And in India, this is being seen as the world once again pandering to Pakistan. And the question that has arisen from this is: well, we thought that the world’s interest in Pakistan ended when that war in Afghanistan ended, when the US and NATO forces pulled out in the way they did in 2021. Now, people are surprised that Pakistan is still relevant. So why is Pakistan still relevant to the world if that is what it is?

The baseline assumption that Pakistan only matters to the world because of its strategic location, etc., has always been proven to be wrong, because Pakistan has reinvented itself from time to time in the sense of what makes it important. And in international politics, a country of the size of Pakistan, with the kind of population that it has, a nuclear weapon kind of endowed military, is not going to be treated as an absolute outlier in the way that we may want Pakistan to be treated.

In fact, I noticed even during this crisis, there was a lot of hand-wringing, saying the IMF has approved the loan for Pakistan, etc. That’s not the way international politics works. Every sovereign country has its own position, has its own rule. In the past, the United States needed Pakistan for a variety of reasons. During the Cold War, Pakistan was a frontline state as far as keeping an eye on certain aspects of Soviet Central Asia, etc., is concerned. Subsequently, in 1971, Pakistan was very important because it helped the Americans to reach out to China. Which is why in the greatest war that was fought between India and Pakistan, the United States actually stood squarely by Pakistan. But from 1999 onwards, we have seen that the Americans are rather more concerned about the nuclear dimension of this conflict and have counselled both sides to come back and so on.

So, I do not believe that just because the war in Afghanistan has ended, the United States does not have any interest in Pakistan. Please remember that Pakistan has a lot of Chinese military capability. The Americans have an interest in having some window into what all of those and whatnot, because Pakistan also operates their military platforms. So, it will be naive and hasty of us to assume that Pakistan is somehow going to be dumped by the rest of the world and that everyone is going to line up against Pakistan in quite the way that we want.

As far as China is concerned, they have the highest geopolitical interests in keeping Pakistan in place. Pakistan is important to them in order to maintain a degree of balance with India and the subcontinent. Pakistan, through the CPEC corridor, etc, gives them overland access to the Indian Ocean Region, which is absolutely important. They do not have it through any other country. And as they say repeatedly, Pakistan has been an all-weather friend. In fact, the China-Pakistan relationship has weathered all kinds of ups and downs. So why should we expect, therefore, that [for] the rest of the world, Pakistan is a kind of a basket case. No country is dismissed in quite this way.

The other question that arises from this is: why does the world not recognise that Pakistan uses terrorist proxies, or that the efforts the world has made, such as the Financial Action Task Force, or designating various terrorist groups that operate from Pakistani soil? Why has all that not worked? Is the world not putting enough pressure on Pakistan to get rid of this whole dalliance with terrorist proxies or their use as a strategy?

Again, the international action against terrorism requires work along several prongs. And it is not always clear that everything moves in the same direction or at the same pace as a country like India will. Which is why in the fight against terrorism, diplomacy is actually at least as important as the military dimensions of it. We have to continually not just catalyse international action against Pakistan, but make sure that the normative consensus is built up against terrorism.

Because, one of the things that we should concede, if you look at the statements given by practically all the countries in this crisis, everyone has outright condemned what has happened as an act of terror. We didn’t see, for instance, a kind of language which would be used perhaps in the 1990s, saying “oh, some people are freedom fighters, while for you they are terrorists”, etc. So that normative consensus is an important one for us. We have to sharpen it. Pakistan has its own geopolitical allies. The threshold for action in international fora also tends to be higher than what we may unilaterally want to declare and so on.

For instance, the demand for evidence. In India, the public opinion is what evidence? Its evidence is all there across Pakistan. So this whole demand for evidence by the international community also angers the Indian public. But in the Indian leadership also it is seen as a tiresome kind of request that this is already obvious to you. Why should we keep on putting forth more evidence? And whatever evidence you put to Pakistan is simply not enough for Pakistan to act on this.

I agree that Pakistan has only very limited interest in wanting to delink itself from this infrastructure that it has assiduously created over several decades and deployed against. So we should be careful. But at the same time, international pressure can increase or decrease. It can be more or less in different areas. And however tiresome we may find it, we have to do it. Issues like Kashmir terrorism emanating from Pakistan are problems that cannot be solved. There is no scalpel that will surgically get rid of this problem for us. We can only manage this problem. And in managing this problem, diplomacy is an important tool in our kind of statecraft. And if we do not manage it, then you’ll have to endure the consequences of it.

So, the first thing we need to do is to educate public opinion in this country that does not seek easy solutions. There are no easy solutions in international politics, as there are none in life. And that we have to learn to deal with these things and to be able to have a measured sense of what we can accomplish under what time frame.

Also Read | Pahalgam attack—this is a policy failure; this is a propaganda failure: Ajay Sahni

The other thing is that you said that it’s very difficult to solve this whole thing with Pakistan. But how have we missed doing something in Jammu and Kashmir that could actually help us prevent these incidents? Not in terms of just security or intelligence, but is there something political that we should be doing and that we have not done that would actually lessen these incidents?

Well, if we take the government’s own framing of what is the trajectory of Jammu and Kashmir since 2019, then clearly things have been getting better. The economic situation has developed. There is more interest in not just tourism, but in other kinds of investment. In Kashmir, we want to have more integration of the Kashmiris economically with India. And in this, after the Pahalgam terrorist attack, we saw a somewhat unprecedented upsurge of popular protests against the terrorist attack, which, for anyone who has been following Jammu and Kashmir, you would concede as a new sort of phenomenon to be confronted with. We have not seen something like that in a while. And that definitely offers us a window of opportunity to bring the Kashmiris more to our side.

At the end of the day, issues like insurgency, terrorism are fundamentally about the hearts and minds of the Kashmiri people. That is what we are fighting for. We want their allegiance. We want them to feel that they have to be with India rather than supporting those who are inimical to our [interests]. It is important, therefore, that we still have the window of opportunity to take this forward and do it.

The other thing—and you were hinting at it in your question on bipartisan diplomacy— is that our position on diplomacy with Pakistan has become more or less that diplomacy is a reward that we will give to Pakistan for good behaviour. In my opinion, that fundamentally misunderstands what the nature of diplomacy is. Diplomacy is there to manage very difficult relationships. It is a very important thing for us to have, whether we agree or disagree. Even countries that are at war with each other typically tend to have close diplomatic engagement and contact. So, by saying that we will not talk to Pakistan at all, or that talks and terror cannot go together, that is true at the level of saying that we do not accept terrorism. But by saying that we will cut off all diplomatic engagement with Pakistan or have only a very minimal kind of diplomatic relationship is to deprive ourselves also of certain very important tools, not just of crisis management, but of shaping the relationship in the longer run and managing it.

Again, I am not an optimist who thinks that peace is around the corner and that we’re going to have a solution. But diplomacy has a somewhat different role than what we seem to be imagining it to be. And treating diplomacy as a reward for any other country’s behaviour is to drastically devalue that in our hands.

You mentioned the Indus Waters Treaty a little while ago, and India has said now that there’s going to be no peace dialogue and the treaty remains in abeyance. What repercussions might this have in terms of how this whole crisis pans out?

No, we have said quite clearly and strongly that the Indus Waters Treaty will remain in abeyance. It will take us a while before we can actually, even if we want to, make systematic efforts to divert flows of water to Pakistan, etc. There are things that we can do in the short run. For instance, we can stop sharing real-time data of water flows. We can even resort to other things like flushing out our reservoirs, which will make life somewhat miserable for Pakistani farmers downstream because you can push out a lot of silt, etc.

But beyond those kinds of things, which will only be sort of pokes and pressures, if we want to systematically deprive Pakistan of any of this, it is going to take us quite a bit of time and thinking to be able to actually come up with all of that. And I do not believe that the Pakistanis will take that kind of a position lying down. Agriculture is a very important part of the Pakistani economy. I think it accounts for about 40 per cent of their GDP. It employs about 40 per cent of their workforce. As a lower riparian, Pakistan has every interest in securing this. So again, there is an element of hyperbole in the Pakistani response to say that we treat it as an act of war. It’s a bit like India saying we’ll treat terrorism as an act of war.

So yes, this is an issue, but my broader concern is that whether it is India or Pakistan or Bangladesh or even China, all countries which have waters flowing out of the Himalayan watershed, with the climate crisis looming and actually on hand and creating new kinds of challenges for us practically with every season, collective action on climate problems and issues is actually going to be a much greater imperative for the subcontinent. In fact, I would go so far as to say that perhaps in the medium-term future, it will be even more of a challenge for us than issues like terrorism. So, if we sort of walk away from the Indus Waters Treaty or refuse to abide by whatever provisions there are, even for renegotiating—the treaty itself has provisions—that will require us to go back to diplomacy rather than walk away from it. And signalling that we are not interested in any form of collective action will make things much more difficult for all these countries in the region, including us.

Again, see vis-à-vis China, we are the middle riparian on the Brahmaputra. We have concerns about the Chinese announcements of all kinds of things. For years, we’ve been saying the Chinese do not share river water data. Now going forward, all of these problems are going to get much more accentuated and aggravated and will assume a magnitude which will affect common people across this region in significant ways. So, our willingness to walk the road of collective action on these kinds of questions could be damaging to our own selves, also. So it’s something we need to bear in mind as we think about what are the next steps as far as the Indus Waters Treaty is concerned.

When you talk about climate change and water shortages and all the other things that are likely to happen, one of the things that the Kashmiris have been saying is that this is going to be a huge problem for that particular region because they are in the Himalayas. And that is where all this is happening. And they are saying that we, in this conflict between India and Pakistan, don’t have a voice. Why are we being denied this? Is that not a fair demand?

It is a fair demand in a sense that any of these kinds of projects will have to take the interests of local populations into account. But again, you know, it’s worth remembering that the Kashmiris are actually opposed to the provisions of the Indus Water Treaty for a long time now because it puts restrictions on how India can use the waters, particularly of the Chenab and the Sutlej. So there have been calls… There was a resolution adopted by the Kashmir Legislative assembly in 2003 when they said that the Indus Waters Treaty must be revisited, etc., because they feel that the State is being deprived of other kinds of energy resources which could come if India were willing to harness these resources more. And there are limitations that the Indus Water Treaty places. Of course, in the new present context, there are other kinds of problems that the Kashmiris are facing and they will face.

So whichever way you look at it, collective action, which involves multiple stakeholders is the only way forward for us as we deal with our neighbours or with States within India when it comes to the climate crisis and its implications. So whatever the temptation to use the Indus Waters Treaty as a point of pressure against Pakistan, we should think about what the medium and long term consequences could be.

Not just the Indus Waters Treaty, but the Kashmiris think of themselves as a stakeholder in this entire conflict, as in how can India and Pakistan decide the fate of Kashmiris? That even when India and Pakistan discuss diplomacy, they are not at the table. Is that not a demand that has to be addressed at some point?

Well, it is certainly the case that the Kashmiris are, as the State embroiled in this particular conflict, central to the way that this particular dispute plays out. And we are at this point of time in a situation where Jammu and Kashmir has been reduced to the status of a Union Territory. The government has already promised that statehood will be restored. Perhaps moves in that direction are now the first steps that we will need to take in order to create a new matrix within which we deal with Pakistan and do not allow Pakistan or the terrorist organisations to weaponise the Kashmir problem against us. I do see that there is a window of opportunity. It depends on whether we have the political kind of sagacity and wisdom to be able to move in that direction.

Nirupama Subramanian is an independent journalist who has worked earlier at The Hindu and at The Indian Express.