In her short introduction to the story “Borges and I” by Jorge Luis Borges, the essayist Maria Popova writes: “… inseparable as the parts may be from the whole, we each contain multitudes—not only psychologically, but even biologically—nowhere more so than when it comes to the bifurcation between our inner and outer selves.” For each of us, Popova adds, there is a public persona encasing the private person, an aspirational self radiating from the real self. Most autobiographies and memoirs are a conscious rearrangement of life, an attempt to present a life that is examined, as also an inquiry into being and appearing. To be able to read an autobiography well is to also be able to read the being-appearing equation as it pans out in any narrative.

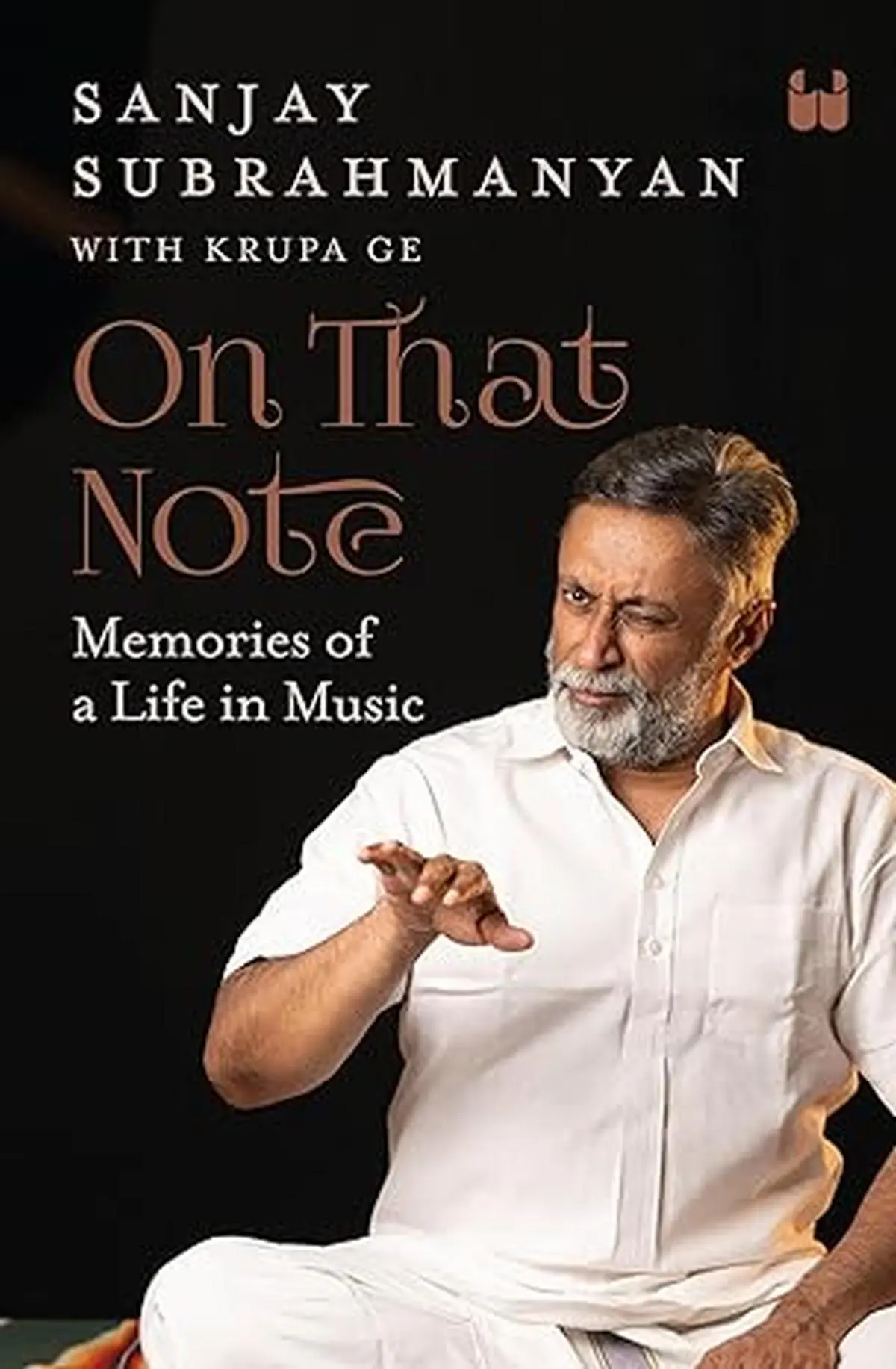

On That Note, the engaging memoir of the eminent Carnatic musician Vidwan Sanjay Subrahmanyan as narrated by Krupa Ge, is a well-thought-out unpacking of musical memories in 11 chapters, presented in a deftly crafted narrative arc, with a tone that is honest. This memoir is not an overflow of emotion but one recollected in tranquility, working within well-drawn boundaries.

The title of the book is also the title of the series that Sanjay launched on his YouTube channel in 2021. The teaser to the series, which ran for two seasons and had 33 episodes, said: “Every raga has a note, and every note has a memory, and every memory has a story. I have many stories to share with you.” The memoir, like the series, has several stories, fuller, richer and longer: “Here I am, on that note, telling you, my reader, the whole story, from the beginning, as I continue in my grandfather’s and mother’s footsteps, narrating the story of my life thus far.”

Also Read | 2,000 hours of Indian classical music

However, for many of us who may have asked ourselves if it isn’t too early for him to write a memoir, Sanjay reasons: “When I read Charlie Chaplin’s luminous My Autobiography in the 2010s ….it felt close to the bone. My interest in history and biographies has only grown with the years. So, I told myself I would write one at seventy-five—after all, the comic genius had waited that long to publish his autobiography. Surely, I needed at least a few decades more in the arts to be able to talk about my life and work!”

However, the pandemic, Sanjay says, changed everything, even what he thought of his music: “I felt the urge to reflect on my journey, on this metamorphosis, to weigh things up, not just look back at a life lived near the end of it. It felt like an immediate need.” With this preamble, Sanjay sets out to narrate his musical journey. “The Great Pause” of 2020 forced individuals, communities and humanity at large to look inward, and responses seemed to emerge from the core of one’s being. The process for Sanjay however, had begun in 2015; the COVID pandemic perhaps accentuated it.

The memoir opens in the now, with Sanjay deciding to don a broad hat—which is to become a “singer” from being a Carnatic classical musician. After he was awarded the Sangita Kalanidhi—an award that is the dream of every Carnatic musician—in 2015, Sanjay speaks of intense moments of rethinking: “The book is an attempt to rethink many deeply held ideas and beliefs.” It almost seems like the book is a canon unto Sanjay himself, establishing, ordering and validating his own thought processes as he records his journey.

On That Note: Memories of a Life in Music

By Sanjay Subrahmanyan with Krupa Ge

Westland Non-Fiction

Pages: 176

Price: Rs. 599

“It Takes a Village to Raise a Musician” is a chapter that takes you through Sanjay’s young years. Both his grandmothers, who played the veena and violin respectively, were deeply invested in Carnatic music. Sanjay’s mother, also trained in Carnatic music, instilled the love of music in him and sent him to violin classes. Favourite musicians, memorable concerts, conversations on music, music lessons, competitions, prizes, vocal training—this chapter is filled with vivid details. What stands out, however, is the young Sanjay’s passion to learn more music, to the point of being obsessed with it. Sanjay’s seeking, as it emerges from his narration, was free of frills. Kutcheris, fame and all the accompanying accoutrements were not part of his early plan, but when they came his way, they pushed him to learn more.

The making of Sanjay’s music was never his alone; there is a warm remembrance of immediate family members, friends like the Sriram duo (Sriram Krishnan and Sriram Gangadharan), Unnikrishnan, Uthirakumar and several others whohelped him cross his musical hurdles in his formative years. At 19, Sanjay gave his first concert, but as he writes, it was to a near-empty hall: “Even though the crowds at these concerts were often disappointing, performing at each venue was still an important experience in that early stage of my career. Singing, experimenting on stage, working with accompanists—I enjoyed all of it. Meeting musical friends, discussing ragas, jamming, learning, asking them what they’d recently learnt, discussing kanakku and listening to tapes, this was the world I was a part of.” His guru was Vidwan K.S. Krishnamurthy (KSK) whose “modernity and how he blended it with his traditional background” left Sanjay completely blown away. An immensely generous guru and a creative facilitator, KSK gently pushed Sanjay to think in the right direction. This chapter makes for a lovely read; of a young boy chasing music fervidly.

‘Tamizhum Naanum’

The coming together of things is always not sequential, it is in the way we comprehend it. Ideas are sown quietly; they blossom much later. The chapter “Tamil and I” is full of serendipitous moments that lead Sanjay to new journeys. The meeting with the theatre personality and filmmaker Prasanna Ramaswamy, the documentary Aaraar Asaipadaar, moving closer to the Tamil intelligentsia—all this triggered a latent passion in Sanjay. For nearly six years, he immersed himself in Tamil literature, meeting writers and building a new repertoire of pallavis and poems for Carnatic music. His grandaunt and guru Rukmini paati, he acknowledges, was responsible for opening up “her vast world of Tamil songs”, because she believed that it would give the young Sanjay an edge in the competitions. His interest in the veteran musician D.K. Jayaraman’s repertoire, the gems in his own guru KSK’s reserve, his manasika guru (spiritual mentor) Papanasam Sivan’s disciple Balu—Sanjay makes sure he has all of it in his collection.

The Margazhi Maha Utsavam was a turning point in Sanjay’s development of the Tamil repertoire. In the years that followed, Sanjay was “immersed in volumes of Papanasam Sivan’s compositions”. The singing of arutpas inspired by the renditions of the mridangam maestro Guruvayur Dorai, the compositions of Dandapani Desigar, the Divya Prabhandam, Tamil padams, Kavadi chindu—Sanjay expands his collection with an interest and perseverance that is rather remarkable. When he began the Tamizhum Naanum (“Tamil and I”) concerts, it was a “cultural shift both for me and the audience that respects this effort. It is part of a larger idea I have for my own music. My interest in Tamil music has been taking me in newer directions, and I’m very excited about where it is going next.” If one part of his relentless research and learning in the Tamil realm expanded his musical horizons, Sanjay also says that it gave him “access to other lives” and “sensitised me as a human being in a very big way because it exposed me to a wide variety of Tamil subcultures that I was completely oblivious to.”

On That Note, the engaging memoir of the eminent Carnatic musician Vidwan Sanjay Subrahmanyan as narrated by Krupa Ge, is a well-thought-out unpacking of musical memories in 11 chapters, presented in a deftly crafted narrative arc, with a tone that is honest.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

The chapters take you through various phases of Sanjay’s artistic development, and the contribution of institutions and individuals to it. In the chapter “Radio Days”, Sanjay speaks of his father, a compulsive radio listener. From consuming huge amounts of Carnatic music on All India Radio (AIR) to becoming a graded artiste himself, the chapter captures a wealth of detail. If AIR was a source of learning, there were zealous family members and close friends who honed Sanjay’s music. Sanjay proclaims his fascination for his long-time violin accompanist Nagai Muralidharan’s modern aesthetic framework. Of his mridangam player Neyveli B. Venkatesh, he says: “Venkatesh is like a metronome on stage. I don’t need to think about rhythm because he is in perfect sync with my singing…. We feed off each other’s energy on stage…”

The others Sanjay looks up to are his friend and confidante Prince Rama Varma and V. Sriram, both strong creative influences on him. He doffs his hat to the great masters—G.N. Balasubramaniam, Rajarathnam Pillai and M. Balamuralikrishna—from whose music he incorporated elements into his own, his collaborations with Sean Roldan and Girishh Gopalakrishnan—Sanjay begins to see the formation of the nuevo in his performances, moving away from “being a strict conservative”.

“I knew my voice had rough edges,” he admits, without making any effort to conceal flaws. Sanjay’s voice gave him many problems and he always had doubts as to how his voice would fare on a particular day. “I have never had a good opinion of it, to be honest—always thought of it as my weakest attribute.” Sanjay rates his December 2023 Music Academy concert as his “worst season performance”, something that continues to trouble him. His uninhibited assessment of his voice is complemented by his ability to interpret music, which he says gave him confidence.

Sanjay who, in the 1990s, was greatly excited about singing for albums and CDs, started his own label, Sahana Sounds. But after a decade, the excitement wore off. Sanjay asks himself, “What had changed?” He finds his answer: the studio had begun to make him feel inadequate, especially about his voice. “The recording studio throws up your inefficiencies, highlights and magnifies them. This same fear was what held me back from singing in films too…” Sanjay currently works with a voice therapist who has been helping him understand how he can use his voice in a scientific manner.

Spirit of collaboration

There are little peeks into the politics of the sabhas, the high-handedness of sabha secretaries, the arbitrary nature of choosing artistes, and how many of these problems get sorted out once a musician makes it to the Music Academy stage. In his current dispensation, the new is important for Sanjay, as is the penchant to move away from what he strongly perceived as his bastion in the past. He writes with excitement about his work for Coke Studio Tamil. The memoir goes into details of his work with Sean Roldan, Ilaiyaraja and others. Marking this remarkable change in his outlook to life and music, Sanjay avers: “All my life, I have thought alone and I have sung alone. Now I find myself seized by the spirit of collaboration; finding new ideas, working with other minds, especially younger ones.”

The chapter “Partners in Time” is a warm ovation to his wife, Aarthi. In a life filled mostly with music, Aarthi brought the much needed intellectual stimulation. A friend and confidante, it is clear that Aarthi is the backbone of his musical expedition, and the in-house editor.

What is remarkable about Sanjay is his other interests, which he takes just as seriously, such as his passion for cricket, for which he chased BBC and ABC broadcasts. He is an avid reader of Sportsweek, Sportstar and The Hindu, and is equally interested in basketball, tennis, rugby and ice hockey matches. He is an avid reader, and his favourites range from Shakespeare to Thomas Mann to P.G. Wodehouse. When his interest in Tamil literature blossomed, he obsessively read every writer from the ancients to the modernists, from Sundara Ramaswamy to Perumal Murugan. Parts of the book which narrate his interest in board games are a delight: Sanjay has over 450 board games in his personal collection, some of which he has played over 200 times! He has tried his hand at philately, gone hunting for Indian ebonite pens. Sanjay is a man of many parts, with music forming his dominant persona.

What you hear throughout this memoir is the voice of a thinking musician constantly assessing himself and his art. The memoir maps the journey of how a young Carnatic music enthusiast shaped himself to be among the leading Carnatic vocalists of today. The voyage in itself is charming; it is also of importance to youngsters to understand the doggedness of the pursuit, its ups and downs, and to never give up despite disappointments and failings.

At one of Sanjay Subrahmanyan’s Tamizhum Naanum concerts, which he says was a “cultural shift” both for him and the audience.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

Sanjay is someone who revisits his decisions time and again; he retains those that remain relevant and discards or modifies others, even the successful ones, that he thinks have changed with time and context. There are many examples for this in the memoir—such as his decision to reduce the number of concerts he sings in a year from 140 to 90 over a period of time, for which he offers a rationale. Sanjay’s ability to relentlessly pursue goals and to do them without seeking validation from an external world are huge takeaways about his persona.

Why was the memoir a more appealing form to Sanjay? He belongs to a generation that occupied the centre stage of Carnatic music following the great masters. It would have been interesting to understand the dynamics that existed, the personal and collective negotiations, fellow musicians and their artistic pursuits. How did Sanjay and his contemporaries shape a new aesthetic for Carnatic music? How did the changing patterns of consumption and dissemination impact their music? Did intense competition and abundant opportunities change the musician forever? These and such questions would have been interesting to understand from a musician who has been singing for nearly four decades now.

Also Read | The saint, the song, and the social revolution

In its current form, On That Note is completely in control of the protagonist, Vidwan Sanjay Subrahmanyan. It revolves around him and only those individuals who continue to remain in his world that he opens up for the reader. Hence, like most memoirs, while it is a candid account of a life, it is also a reflexive crafting of select episodes and perspectives. The aesthetically rearranged memories present an examined life, but how much does it leave out? The form in itself comes with the insistence of the fullness of a partial view.

Let us return to “Borges and I”, where Borges writes: “I walk through the streets of Buenos Aires and stop for a moment, perhaps mechanically now, to look at the arch of an entrance hall and the grillwork on the gate; I know of Borges from the mail and see his name on a list of professors or in a biographical dictionary. I like hourglasses, maps, eighteenth-century typography, the taste of coffee and the prose of Stevenson; he shares these preferences, but in a vain way that turns them into the attributes of an actor. It would be an exaggeration to say that ours is a hostile relationship; I live, let myself go on living, so that Borges may contrive his literature, and this literature justifies me. It is no effort for me to confess that he has achieved some valid pages, but those pages cannot save me, perhaps because what is good belongs to no one, not even to him, but rather to the language and to tradition.”

You can hear resonances of Borges in On That Note too. Sanjay is tough on himself. It would be wonderful, if at 75, there will be a biography, with a fuller view on the world of Carnatic music vis-a-vis Vidwan Sanjay Subrahmanyan. It is imperative in a polarised world to examine people and processes dispassionately.

Deepa Ganesh teaches at RV University, Bengaluru.